- Like

- SHARE

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Flattr

- Buffer

- Love This

- Save

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- JOIN

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

(Original Caption) Illustration depicting Commodore Matthew Perry (1794-1858) meeting the royal … [+] commissioner at Yokahama, 1853. Undated painting.

Bettmann Archive

- “Japan’s sogo shosha …Japan’s trading companies… swashbuckling adventurers, the original globalizers of Japan… Their interests extend worldwide from snowboards, silk scarves and souvenir banana cakes to hydroelectric megaprojects, chemical plants and oil exploration. One of them is the world’s biggest handler of endangered bluefin tuna; another had its management system forged in a Siberian prison. One has just installed garden swing-chairs to help its executives think; another was responsible for one of history’s worst trading scandals. A fifth has Botticelli’s La Bella Simonetta hanging outside its boardroom. But as of this week, the five biggest — Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Marubeni and Sumitomo — have something in common: Warren Buffett as a shareholder.”

Warren Buffett’s Japanese gambit last month was “huge,” visionary, exciting, baffling, troubling – the usual range of responses from the gallery when Buffett makes a big bet that no one was expecting. But this $6 Bn “foray” into the murky world of these ancient Japanese trading companies violates many of his own investing principles. It belies his previous pronouncements on the problems with Japanese investments. It is his largest ever investment outside the U.S. – but the investment thesis is unclear. And it follows a string of “blunders” (see below), which raise the question: Is this, once again, an expression of his enigmatic genius which will in due time show itself to have been a brilliant move? – or is he finally losing his touch? Does his “value” strategy still work?

The Case For Genius

“Buffettology” is a faith-based enterprise, which rests upon his extraordinary track record over five-plus decades.

Consider: Since the 1980’s (when Mr. Warren Buffett of Omaha, Nebraska, became The Warren Buffett – Wall Street titan, celebrity financier) the stock market is up 2300%. Which sounds pretty good.

Berkshire Hathaway is up 74,000%.

- “The S&P 500 has delivered annualized returns averaging 9.7%. Berkshire Hathaway has generated an average gain of 20.8% per year… Since Warren Buffett took the reins of Berkshire Hathaway about 52 years ago, Berkshire’s stock has delivered 155 times the total return of the S&P 500.”

How does he do it? The mantra has been “Value.” In the public’s mind, Warren Buffett is the icon of “Value investing.”

So, what is “Value” exactly and do the sogo shosha qualify?

Value Investing

Japan is said to abound with cheap companies with solid business prospects, trading at low prices relative to intrinsic value, offering rich dividends, with improving governance, stronger shareholder protections, all against a stimulative macro-economic policy from the government – in short, a market ripe with “value plays” of the sort that Buffett has traditionally sought out. A lead editorial in the Financial Times gushed:

- “His sudden, seemingly contrarian, interest deserves the attention of an investment community that has long shunned the world’s third largest stock exchange. Foreign investors have been net sellers of Japan for almost five years, and remain underweight in global portfolios. For brokers, who have been hammering away with the pitch that solidly-yielding, low price-to-book Japanese equities represent the best value in the world, Mr Buffett’s $6bn move could have huge implications.”

“Value plays” exist because a company is “unattractive” for some reason, out of favor, perhaps in some distress. For example, right now some companies in the Energy sector are seen by many as “value plays” – the sector is depressed by the pandemic impact on energy use, and the supply/demand imbalances and low prices of crude oil. Exxon and Chevron have lost nearly half their market value in a few months. They are awash in pessimism. The value thesis would be that an economic recovery, as well as corrective adjustments by the companies in question, will restore investor sentiment to a more confident perspective and lead to a recovery of the share prices. Stated simply, value investing looks for a company that is mispriced, undervalued by the market, but otherwise seems solid. The play is to buy and hold, and wait for the market’s perception to change. If the market eventually recognizes its “mistake” and corrects the mispricing, it will create a tail-wind to boost the formerly out-of-favor company’s share price much faster than its earnings growth.

It is that “eventually” qualifier that makes “value” tricky. It may take a long time before the market makes this correction. Or it may never correct, if there are good reasons for low valuation – an obsolete business model, or poor corporate governance and insecure shareholder rights.

How “Value” Metrics Work

To find “value,” most investors start with the basic metrics, such as Price/Earnings ratios, and Dividend Yields. Why do these ratios matter? How do they signal “value”?

Dividend Yield

Dividend yield is the ratio between the current annualized cash dividend per share (for a company that pays dividends) and the company’s current share price. The market’s valuation (share price) is in the denominator, so a low share price – perhaps indicating an undervalued company – will drive the dividend yield higher. High yield is the “value” signal.

The P/E Ratio

The Price/Earnings ratio is the ratio of the company’s share price to its earnings per share. There are many versions of this ratio. In the most common, “earnings” refers to the company’s net profits (according to GAAP accounting) from the past 12 months. Low P/E is the value signal.

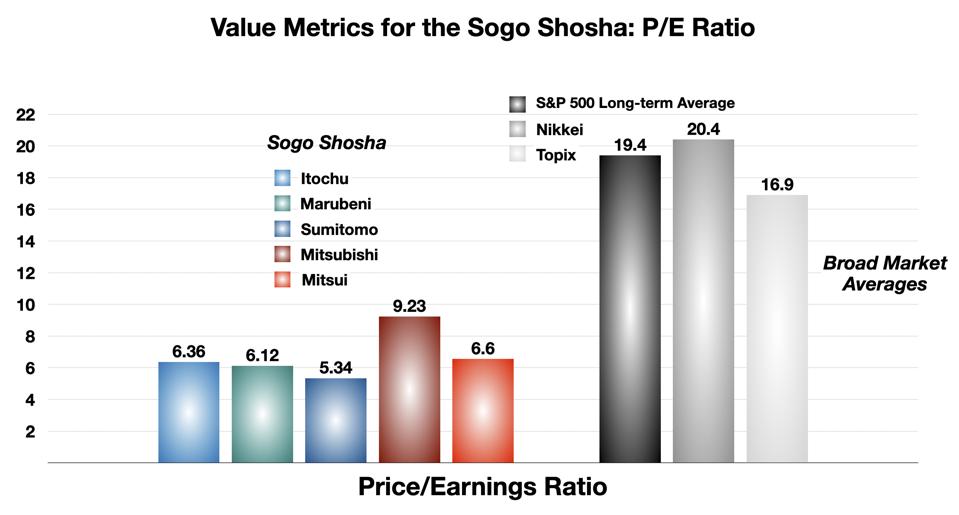

By these measures, the sogo shosha are severely under-priced, classic “value stocks.”

Sogo Shosha – Low P/E Ratios

Chart by author

Sogo Shosha — High Dividend Yields

Chart by author

Interpretations

The problem is that these metrics are signals of possible “value,” not definitive judgments. They need interpretation.

Dividend yield is more straightforward, and probably more popular than P/E for screening companies to find underpriced “value plays.” For one thing, the payment of a dividend is a real cash-in-hand event that is not subject to the vagaries of the accounting rules governing the calculation of “profit.” Earnings can bounce around for lots of reasons, some of which are “real.” (Some are based on accounting conventions, which can change.) As well, a high dividend is comfort-giving for the value investor while he/she waits for the investment to pay off.

The P/E is so commonplace that most investors don’t think about its peculiar nature. It is actually a chimera (“a mythical animal with parts taken from various animals.”) It involves an explicit comparison of incompatible data types – “apples and oranges” (to add a metaphor from the vegetable kingdom). The numerator comes straight from the stock market. The denominator is the accountant’s measure of the company’s net profit and has nothing to do with the stock market. The P/E is effectively a forced comparison of non-comparable quantities.

It is a strange metric that can be interpreted in several ways. From one perspective, it is a measure of how much value the stock market awards a company for every dollar of earnings. For example, Sumitomo here is credited with just $5.36 of market value for every dollar of earnings. If it earns another $1-per-share next year, you would expect its share price to increase by $5 or so. By comparison, the market grants Facebook over $30 in share price value for every dollar (per share) it earns. If it earns the same $1-per-share extra next year, its share price would rise – all things equal – by $30.

A “Value strategy” comes at it from a different angle. A claim on a $1 of Sumitomo’s earnings costs you just $5, while Facebook’s $1 of earnings goes for $30. In this view, Sumitomo’s performance is undervalued – mispriced by the market. It is “cheap” (and Facebook is “expensive”). The market average P/E in Japan is much higher, in the range of 17-20.

By these measures, this looks like a standard Buffett investment: good companies at a cheap price. The superficial case for “Value” here seems strong. So – In Warren We Trust?

The Case Against

But the skeptics (who, like the poor, are always with us) carp away. They point out inconvenient facts. First of all, maybe Buffett has become – simply – ordinary, of late.

- “Over the last decade, Buffett’s track record has been decidedly average. In fact, over the last ten years Berkshire has actually slightly underperformed the S&P 500 on a total return basis.”

BRK Over the Last 10 Years – Just Ordinary?

Chart by author

Ordinary is one thing, but has he has “blundered” again?

- “What have the nearly 90-year-old Buffett and his 96-year-old business partner Charlie Munger done for us lately? … Three of Buffett’s biggest recent investments—Kraft Heinz, Occidental Petroleum, and airline stocks—have lost at least $7 billion altogether out of an investment of roughly $10 billion in each.”

Worse still, has he deviated from his own standards? The skeptics argue that the deal “makes a mockery of the investment principles he has stuck to all his life.”

Consider the following “violations” of the Buffett principles.

Lack of Clarity?

Buffett has many times argued that one should look for businesses that are simple, comprehensible, and transparent. None of those words apply to the sogo shosha:

- “Buffett famously likes his businesses simple to understand and transparent. Why, then, has Berkshire Hathaway, poured $6bn into Japan’s trading houses [which] do not appear to meet either criterion? They run a bewildering array of subsidiaries in most sectors of the economy.”

These companies’ business models lead them to construct elaborate cross-ownership networks.

- “Buffett’s “easy to understand” mantra hardly applies to trading houses whose complexity is notorious. Sumitomo, for example, has holdings in 87 other listed companies. Mitsubishi, 182.”

In fact, they are similar to Berkshire itself – unruly conglomerates that lacks any real strategic framework (to be honest about it). The only thing that links the components of Berkshire’s portfolio is Warren Buffett’s magic touch. But the sogo shosha aren’t run by Warren Buffett, but by teams of Japanese salarymen whose names no one knows.

No Moats?

Buffett has said that what he looks for in a company is a “moat” — a defendable franchise based on hard-to-duplicate assets that create a strong barrier to potential competitors – such as Coke’s brand equity. Whether these Japanese trading companies have “moats” of this sort is unclear. The volatility of their business puts this in question. The Economist tells us that “the trading houses fail dismally” to achieve moat-status. They may not even be all that profitable, in terms of return on equity.

- “The trading houses’ heavy dependence on revenue from commodities means they do not have the “moat” — a competitive advantage over peers — that Mr Buffett tends to favor. Several of the trading houses also have accounting or operational hiccups in their recent history. And if the Sage of Omaha truly likes high returns, it is odd that he has selected five companies where only one has a five-year return on equity that is higher than its cost of equity.”

Are They Really Value Plays?

This raises the question as to whether the trading companies are true “value plays.” There could be good reasons for their low P/E ratios, structural flaws in their operations that hamper their ability to generate shareholder value. Fidelity has commented:

- “It’s tricky for investors to determine whether the companies are undervalued… The timeframes for investment returns vary between their businesses, and it’s tough to gauge their overall risk profiles. Their many joint ventures mean they lack full control of their operations, their late-stage investments often have limited upside, and their earnings can be volatile. They have also been forced to write down the value of some assets due to financial crises, pressure on commodity prices, and low interest rates…”

Soggy Cigar Butts?

The deal also contradicts Buffett’s past pronouncements on Japan. At the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting in 1998, he was asked about Japan. His answer:

- “We’ve looked at securities in Japan, particularly in recent years when the Nikkei has so underperformed the S&P here.We’re quite a bit less enthused about those stocks as being any kind of obvious bargains…”

His folksy analysis was brutal.

- “Many years ago we gave up what I’ve labeled the “cigar butt” approach to investing, which is where you try and find a really kind of pathetic company, but it sells so cheap that you think. We used to pick up a lot of soggy cigar butts, you know. I mean, I had a portfolio full of them.”

So, are we back to sucking up soggy Japanese cigar-butts? Or have they morphed into milkshakes?

“Value” vs “Growth” – The Disappearance of Value

As noted, Sumitomo – at its present price-earnings ratio – would add $5 in share price for every $1 increase in earnings. Facebook would add $30 in share price. Which stock would you rather own?

A “Growth strategy” would choose Facebook. The company is very successful. Their high P/E means that if they keep it up, their shares will rise much more – perhaps 6 times more – than Sumitomo’s shares for the same fundamental earnings performance.

Many of the best stock-pickers are Growth investors. Their investment thesis is simple: they expect strong future growth in earnings, and they regard higher-than-average value metrics (e.g., high P/E’s) as a buy-signal.

Moreover – “Value” seems to have disappeared. Since the 2008 crisis, the Value Factor has underperformed in absolute terms, relative to Growth, and relative to the market overall.

Performance of the Value Factor 2010-2020

Chart by author

Relative to the decade-long bull market benchmark, the picture is worse.

Performance of the “Value Factor” Relative to the Global Market Benchmarks

Chart by author

In short, “value” has been a massive fail as an investment strategy of late.

There are two theories here. One camp holds that the market has finally figured out and arbitraged away the pesky mispricing – “Value” is dead as a market anomaly. The other theory is that these charts portray a massive “coiled spring” absorbing more and more negativity – and setting up a huge rebound of value stocks at some point down the road. When the so-called “factor rotation” arrives.

“Value” is in any case a more difficult road. Value investors buy into a stock that is distressed, or out of favor, and play for a return to better times, improved investor sentiment, and higher share prices. In other words, they buy something that is “not working” and hope that it will start working again. They run the risk that it may never work. (A lot of investors in the retail segment are finding this out – viz. JC Penney.) Growth investors pay a high price for stocks of hyper-successful companies like Amazon or Apple because they expect continued strong performance. They don’t mind paying up. It’s an upbeat mindset:

- “High margin, fast-growing, a lot of free cash flow… If a stock has doubled or tripled, you haven’t missed it. If it’s going to be a multiyear period of strong growth, you’ve got to get on board.”

“Growth” is an easier strategy to follow, psychologically. A Growth investor is buying something that works well – and all he/she needs to succeed is that it continue to work well. It’s playing a positive trend. Whereas the Value investor is hoping for a reversal of a negative trend. “Growth” is bet on continuity; “Value” is a bet on change. Continuity is almost always a safer et than Change. “Value investing” is tentative, cautious and lonely. “Growth” investors have a happier outlook, and plenty of company to cheer them along. “Value” is contrarian – which to say, it is not quite rational. It’s a bet against the consensus, and sometimes even against “common sense.”

Japan: Value Play or Something Else?

The sogo shosha deal looks good in terms of the value metrics, and may prove out. But simple metrics are no more than simple metrics. In terms of the fundamentals, the case is less clear. Buffett’s departure from past principles – accepting a complex, non-transparent business model, in a market he has long disdained – is puzzling. And the disappearance of “value” from the markets – as true for Japan as for the U.S – amplifies the doubt, which critics have taken up.

- “[Many] suspect Mr Buffett may come to regret his choice and has taken a plunge into a quintet of companies whose foibles he has not grasped and whose shortcomings he cannot hope to address.”

The Economist is even harsher, with another strong whiff of “ageism”:

- “Berkshire’s shareholders [may] rue Mr Buffett’s nonagenarian adventure.”

It’s a tough business. Tougher for value investors. But then maybe the wily nonagenarian has something else in mind. Has the arch-contrarian has turned contrary to his own contrarianism…?

George Calhoun’s new book is Price & Value: A Guide to Equity Market Valuation Metrics (Springer 2020). Prof. Calhoun can be contacted at gcalhoun@stevens.edu