- Like

- SHARE

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Flattr

- Buffer

- Love This

- Save

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- JOIN

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

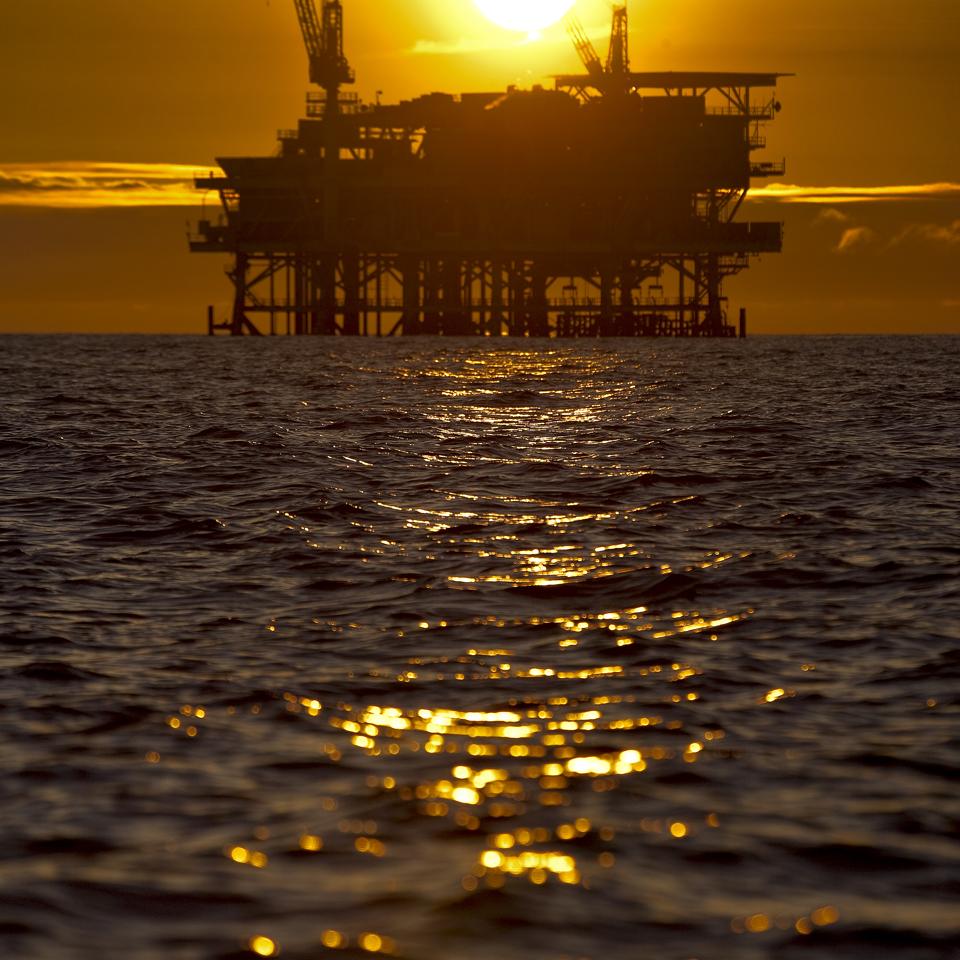

Offshore oil rig, Pacific. Photographer: Tim Rue/Bloomberg

BLOOMBERG NEWS

Who on earth would want to invest in an oil company?

Amid a recession-reduced need for their products and the lingering effect of a supply glut, their stocks are down this year by a third to a half. Crude oil, while recovering from its April lows (it actually had a negative price in April), is still off 30% in 2020.

Exxon

XOM

CVX

Meanwhile, the march of alternative energy continues. In the U.S., solar energy production surged to 90 billion kilowatt hours last year from almost nothing in 2005, and wind power grew to 300 billion, according to the federal Energy Information Institute (EIA).

Still, these so-called renewables are a fraction of the 4.1 trillion total generated in the nation. What’s more, the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow. Solar and wind are pretty much confined to power generation. Electrical vehicles, which are hooked up to the electrical grid, comprise only 2% of the U.S. auto fleet, and IHS Markit projects that will rise to just 7% by 2025. Gasoline and diesel will run the rest, of course.

But the brief for traditional oil-and-gas companies is simple: The fossil-based energy sources aren’t going extinct. By 2050, the EIA estimates, renewables will make up 28% of global energy consumption, almost double the amount in 2018 (15%), making it the leading source, by a hair. Notice, that it’s not 100% or anything close. Right behind it: petroleum at 27% (down from 32%), then natural gas, holding steady over the three decades-plus span at 22%.

Technological advances may yet prove wrong on the projections for continued usage of oil and gas. Maybe batteries will improve dramatically, making massive storage of solar and wind power more do-able. Some believe that the available oil will peak in 20 years, although past dates for peak oil have come and gone before. Also, fossil fuels could be legislated away: Joe Biden says that, if elected, he would push for halving America’s carbon footprint by 2035.

Yes, there’s a strong movement afoot to divest fossil fuel stocks, mainly found among public pension plans and university endowments. You might not want to invest in Exxon Mobil or Shell on moral grounds. Or you might reason that oil and gas are necessary evils, and that if you don’t invest in them, somebody else will. And you might even console yourself that the six super-major oil outfits invest in renewables, albeit their commitment amounts to just 1% of their total budgets, NS Energy calculates.

So should investors really write off the oil industry? No. And in arguing this, I am not leading a cheer for fossil fuels. A world with 100% clean energy, or at least some significant percentage, would be wonderful. Climate change is real.

As things stand, though, since it looks as if these carbon-laden energy sources will be around for some time, maybe investing in them makes sense. Let’s cast aside the moral question for a moment and ask if petroleum and gas are perennial stock market losers. Or whether they are smart value plays that will at some point regain their market mojo and deliver for shareholders.

Economic forces, namely recessions and over-production, are the key factors in the current fortunes of the super-majors and other ancillary companies, such as those that specialize in exploration or manufacturing drilling rigs. The companies’ stock prices and profits, to be sure, usually track oil prices closely.

Take Exxon, the world’s largest producer by market capitalization ($172 billion as of Friday). Its shares peaked at $101 in 2013, then slid 25% by 2015 as a glut sent oil prices skidding. As the over-supply dwindled somewhat, the stock recovered to $93 the next year, but began a slow fall amid the fracking boom, where many independent operators flooded the world with cheap, plentiful oil.

Although the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and Russia agreed to limit production in 2016, the frackers were a constant force bringing the price down. After a falling out earlier this year, OPEC and Russia agreed to once again limit output in the face of the pandemic and its attendant recession.

Now, Exxon stock has stabilized at around $40. Not helping is its $1.6 billion in red ink for the first half. Still, its resources are formidable, easily sufficient to weather the current storm. Cash on hand (helped by floating bonds this spring at rock-bottom interest rates) is $12.6 billion, almost equal to 2019’s net income. Meanwhile, investors can content themselves with Exxon’s dividends. The forward yield is 8.8%. Management is committed to keeping its payouts lush.

At some point, the recession will end. For better or worse, oil and gas will still be in demand. Upshot: If you have patience, buying Exxon or another stock like it may well pay off.